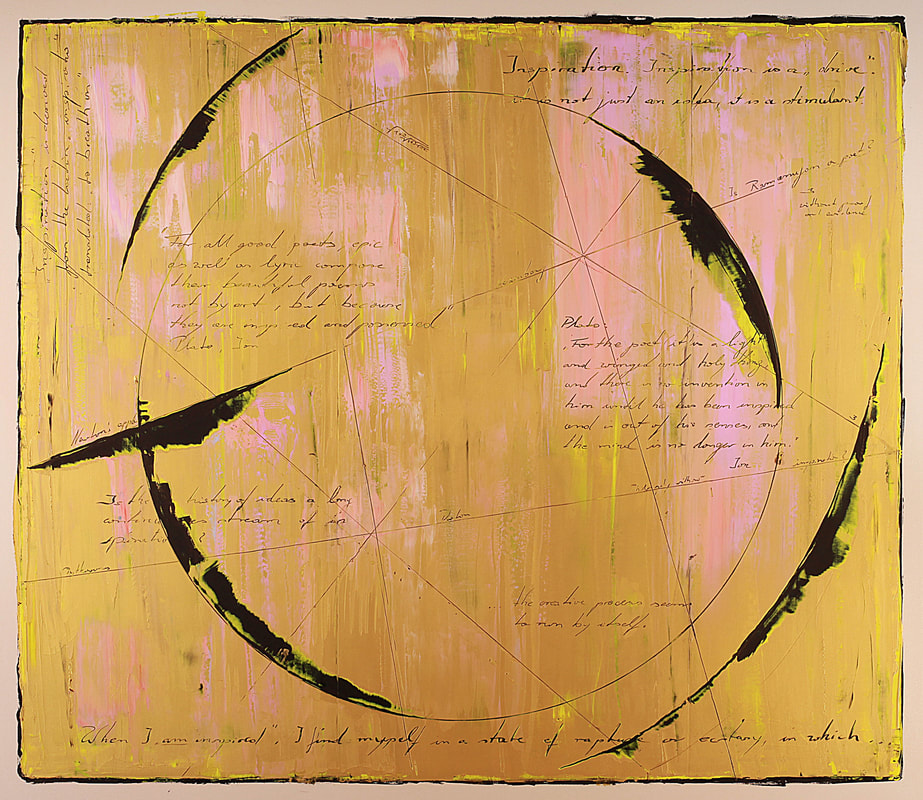

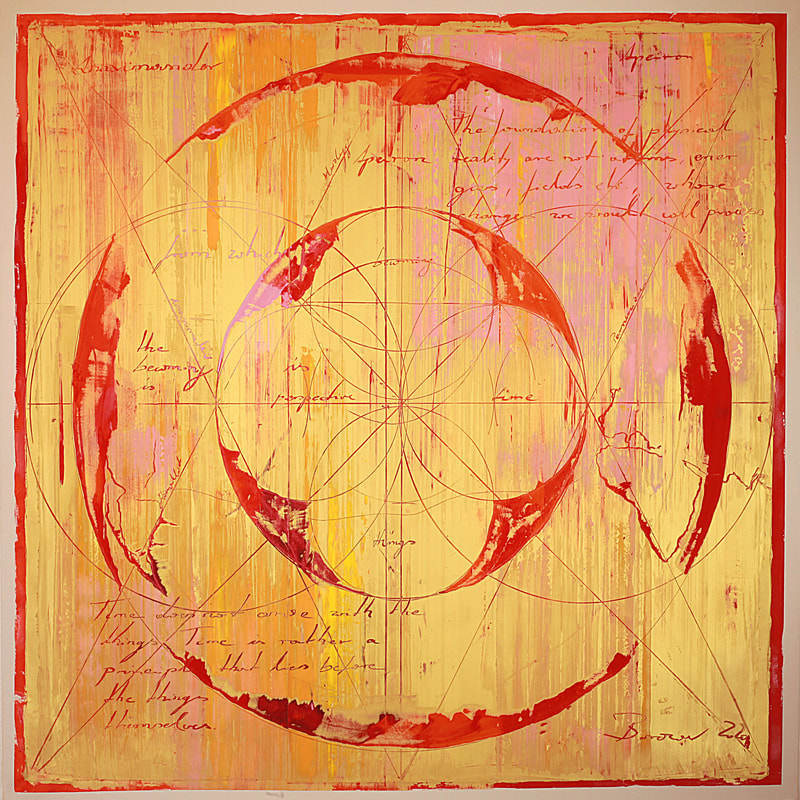

When philosophy is looked at ...Since antiquity, philosophy and art have gone different ways. They always had a close relationship, if not even a love affair, but it rarely came to a union. Since Nietzsche this changed. Philosophy took its way into literature. However, not into the fine arts. But what happens when painting becomes the medium of philosophy? The character of philosophy changes, as well as that of the painting. Philosophy becomes more associative and meditative. And the picture now no longer wants to be looked at, but also read. Rationality meets emotionality.

0 Comments

For an artist, questions are part of the process. Some I'm asked by friends, collectors, and curators, many I frequently ask myself. Questions about technique, composition, about the texts in my paintings, and in particular regarding the combination of art and philosophy. I have compiled the most relevant of these questions and arranged them sequentially. This produced something resembling an interview, which by its openness captures the textual character of my paintings better than a self-contained essay might. Djawid C. Borower _______________________ It appears important to you to combine art and philosophy. How does that benefit art and how does it benefit philosophy? They are already closely related. Art is considered intuitive and emotional, philosophy as rational. Combining art and philosophy creates something that is intuitive, emotional, as well as rational. You refer to your paintings as "palimpsests". How did you arrive at this term? 'Palimpsest' derives from classical Greek. In antiquity, it meant manuscripts that were reused, often more than once, by scraping them clean and then writing on them again. "Palin" means "again" and "psaein" "to scrape". The term describes my own technique perfectly. I apply oil colours in several layers and then, partially, scrape them off again. Apart from that, to me, the term reverberates with a certain mythological depth. As you scrape away, you uncover sections of the underlying layers, revealing colours, shapes, and text fragments. What exactly is involved in creating these layers? In a classic oil painting consisting of several coats of paint, I would make sure that the layers corresponded with and complemented one another. In my palimpsests, however, coherence is not an issue, there can be tensions even contradictions between individual layers. That is part of the attraction. You could say that the structure of my paintings is historical. The bottom layer is a painting in the classic modern style, such as Geometric Abstraction or Abstract Expressionism. This layer is both the foundation of my paintings and a possible point of departure. Don't you regret painting a canvas and then having to cover it up again. If I am particularly happy with the painting, yes, there is some regret. But in the end, it is considerably more exciting to paint over and uncover certain parts. Historical palimpsests are the result of a similar process. Catholic medieval practise was to write over texts of classic antiquity, i.e. "pagan" texts, covering up its own antecedents. Rather than being ostracised, the 'other' remains an integral part of the textual body. I find this inherent otherness fascinating, not least because I believe it exists in every culture and, by extension, in every work of art. The scraping process also reveals fragments of texts. What kind of texts? In many cases, these texts are preparatory studies, notes, excerpts, sketches, for my paintings. Sometimes, they are by authors I am currently interested in. Or it's a passage from one of my plays. In a way, the bottom layer belongs to my artistic subconscious – invisible but nevertheless present. What makes up the topmost layer? The top layer covers the entire surface of the painting. Rather than applying the final images and texts to top of this layer with a brush, I uncover and reveal what lies underneath. In earlier paintings, you used a spatula to scrape off the paint. Do you still do it this way? Yes. Though the process has become slightly more involved. I used to apply only a single coat, today I use several. Nowadays, I dip the spatula into the wet oils and scrape the paint aside. Previously, it was more of a blurring effect. This technique emphasises the procedural and creative character of the composition. Your earlier works were also noticeably more graphical. The traces of scraping aside, there was no evidence of brushstrokes and only very few handwriting elements. Earlier paintings originally allowed me to withdraw behind the work itself. The scraping was my handwriting. Now, the author has returned. I also deliberately sign the facing side of my paintings, which has fallen out of fashion. Postmodern philosophy refers to "The Death of the Author". You do not share this view? Put in a different way, this proposes that every work of art is a product of its time. Postmodernism refers to "orders of discourse" that determine our choices. In many ways, this is true. Nevertheless, in foregrounding handwritten elements, I point to this theory's limitations. Here, the author is undeniably present. In many of the texts engraved in your paintings the „palimpsest” serves as a cultural metaphor. What does that mean? In my view, the palimpsest metaphorically reflects the understanding that past events are not simply replaced and obliterated by subsequent events. On a superficial level, China is a western culture. But underneath the surface, the old China lives on. In Europe, Christianity covered up antiquity like a glacier until to have it resurface during the Renaissance. History resembles a process of shifting tectonic plates that does not happen surgically but rather in a conglomerate of above and below. Development is only linear if you look at it through a brief and narrow time window. Something similar holds true for the texts I use in my paintings. When I quote Plato, I first check my own reaction to his ideas, my emotional response as well as my current interpretation. Below this crust of intuitive understanding, however, lie centuries of discourse on Plato. How were his texts received 100 years ago, how 1000 years ago? How did Plato's contemporaries react to his propositions? Where are the fault lines, the contradictions or, for that matter, the limits of my own conception? As far as I am concerned, philosophy itself is a kind of palimpsest. This sounds like deconstructivism!? My methods are certainly informed by that. But I take my own intuitive and emotional approach as the top layer very seriously. This uncovering of things is a very deliberate and creative act, which allows me to become visible as an artist and the author. Where do the texts in your paintings come from? In the main, I wrote those texts myself. They can be theoretical but also very personal reflecting my own views on a subject. Occasionally I quote other authors. Your paintings make one recall the drawings of da Vinci, which also have a pronounced textual element. Is this deliberate? No doubt, da Vinci is inspiring and I certainly looked very closely at his drawings as well as his texts. But I don't paint the way I do because I think da Vinci is great, but because I am looking for a way to combine painting, handwritten text, and philosophy. The resonance with da Vinci is almost automatic, since in his work he employed, artistic, theoretic, and handwritten elements. Also, people are unusually aware of his work. What artists do you feel you can relate to? As I mentioned, the first layer of my paintings is meant to provide a connection with classic modernism; I'm particularly intrigued by the geometric abstraction of somebody like Malewitsch or by Kandinsky and early colour field painting. Other artists have combined painting and autographs before me, Cy Twombly for example. How do you feel about concept art? Conflicted. To me, it is the 'inner other', the bottom layer which I use as a foundation. Concept art appeals to the mind. However, I myself seek a way for people to have an experience that is simultaneously rational, emotional, and physical. In painting, writing has been a compositional element since Picasso. Your use of text, however, also involves its content. Why do you feel it's necessary to work out your thoughts on canvas rather than on notepaper? A scientific paper is intended to prove an argument. A work of art isn't. It is more open. Unlike a treatise, a painting presents several aspects of a subject simultaneously. It creates an associative space, enabling the viewer to pursue their own train of thoughts. A scientific paper suggests a kind of objectivity that does not actually exist. A work of art, on the other hand, makes it quite clear that it represents the subjective expression of the artist. The relationship between a work of art and its recipient is a great deal more intimate, more emotional and subjective than reading a paper. The book is closed, the screen switched off. If you have a painting hanging on the wall of your home, you can engage with it throughout your life. Is it still appropriate to call this philosophy? It depends how you define philosophy. If you value the scientific method too highly, Plato might stop being a philosopher and turn into a dramatic author. Too much art! Antiquity was abuzz with poet-philosophers: Heraclitus, Xenophon, Empedocles etc. Mathematicians composed approximately a third of their theorems in the form of poetry. Philosophy was recited, rhymed, written, and lived. Only after structured teaching had reached beyond a certain point, did it need to be textual and systematic. But philosophy is not bound by form or medium. So, yes, philosophy can materialise in a painting. What matters most to me is its fundamental purpose. Here I agree with antiquity's view. For Socrates, philosophy was a midwife's art. It wasn't about imparting content, but rather encouraging your own insight. A poem, an aphorism, and a painting can do that. However, many contemporary philosophers believe that their discipline needs to be a form of science!? There's nothing wrong with science. But philosophy can also be something else. It can be much more. During antiquity, it was a life choice. Epicurus had a garden where citizens, hetaerae, and slaves would come to engage in philosophy. Philosophy represented a fundamental decision to perceive the world in a certain way and to live life accordingly. Today's art was antiquity's philosophy. By limiting the latter to science, what remains unaddressed gravitates towards the arts. Something like that is happening today. Once parts of philosophy migrate towards the arts, does that not diminish its analytical capacity? Two and a half thousand years of philosophy saw argument, demonstrations, similes, monologues, oration, or insights with a high degree of plausibility: "Everything flows". In my paintings, I, too, occasionally propose an argument. But I also cite examples and I describe my own emotions. I create systems of references. I create conceptual imagery. However, I do not obsess about making my argument compelling. This marks the difference between my paintings and a scientific paper: A treatise seeks to convey its ideas without ambiguity, a work of art prefers to remain open to interpretation. You quote the history of philosophy. What does it mean to you? Engaging with the ideas of influential philosophers through the medium of a canvas is something completely different than writing a paper on them. The temporal dimension starts to become irrelevant. I address fundamental questions in a discourse involving individuals who lived a thousand or two thousand years ago. As I'm scoring their texts into the oils, I feel like entering into a dialogue with them. Suddenly, their reflections are no longer a thing of the past but exist in the here and now. On the canvas, I can lend them body, colour, and form. Aside from such personal experiences, I believe that philosophy's supratemporal quality is a great advantage. It makes no sense to me to separate philosophy from the history of philosophy. Philosophy itself might also be described as a type of palimpsest. To what extent do your philosophical arguments on the canvas influence your texts? Working on a text on a screen is different from doing it on canvas. The process of painting, the slow engraving of text, the aesthetic aspect of the lettering, as well as the physical sensation, all give rise to different thoughts. There's a different smell, it is more colourful and sensual to express yourself on canvas. The idea finds its embodiment and is imbued with emotion. It is a part of the real world. Certainly, the medium influences my message. Similarly, the act of applying several layers of paints and scraping some off again certainly influences my thoughts on the subject of the "palimpsest". There are also many other theses and ideas that inspire my painting. Conversely, I learn from my paintings, they trigger something in me: a realisation, also on an emotional level. For me, too, they fulfil the role of a midwife's art. copyright 2021 |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed